Most organisations now face a practical choice about how to deliver AI. Should they rely on vendor tools and platforms? Should they build capabilities in-house? Or should they blend both approaches through a hybrid model?

There is no universal right answer. The best choice depends on business needs, risk appetite, data sensitivity, internal capability, and the pace at which the organisation needs to move. It also depends on the kinds of AI use cases being pursued. Some use cases are well served by off-the-shelf solutions. Others need deeper tailoring, tighter integration, or stronger control.

What matters most is avoiding two common traps. The first is assuming vendor AI will solve everything quickly without significant organisational work. The second is assuming in-house builds automatically create competitive advantage, without recognising the operational burden of building, running, and governing AI systems over time.

This article sets out a practical way to think about vendor AI, in-house builds, and hybrid delivery. The aim is to help leaders choose a delivery model that fits real constraints and supports sustainable adoption.

Start by separating tool choice from capability choice

Many organisations treat delivery choice as a tool decision. Which platform? Which model? Which vendor? In practice, the more important question is capability. What capabilities must the organisation own to use AI safely and effectively?

Even with vendor tools, organisations still need capabilities such as:

- Data governance and access control.

- Security review and vendor due diligence.

- Use case selection and prioritisation.

- Governance tiering and approval processes.

- Monitoring, incident response, and change control.

- Workforce training and adoption support.

Vendors can provide technology, but they cannot replace the organisational operating model. When organisations ignore this, they buy tools and then wonder why adoption is uneven or risky.

What vendor AI offers well

Vendor AI is attractive because it can reduce time to deployment. Many vendors provide mature capabilities, documented features, and support models that in-house teams may not be able to replicate quickly.

Vendor AI often works well for:

- Common productivity use cases such as drafting assistance, summarisation, and search.

- Standardised workflows where many organisations share similar needs.

- Rapid experimentation where teams want to validate value quickly.

- Scalable infrastructure where the organisation would rather not manage model hosting and performance.

Vendors also bring updates. They improve models, add features, and expand integrations. This can be valuable when internal teams are stretched and cannot maintain a fast release cycle.

However, vendor AI is not a free shortcut. It still requires integration work, data access decisions, governance, and adoption support.

The real risks of vendor AI

Vendor AI introduces risks that are sometimes underappreciated early in adoption. These risks are not only technical. They are operational and contractual.

Common vendor AI risks include:

- Data handling uncertainty if contracts and technical controls are not clear.

- Limited transparency about how models behave, change, or are trained.

- Vendor lock-in when workflows and integrations become tied to one provider.

- Change unpredictability when vendors update models and outputs shift.

- Misalignment with risk posture if the tool’s features do not support required controls.

These risks do not mean vendor AI should be avoided. They mean vendor AI must be governed properly. Vendor selection should involve security, privacy, legal, and operational stakeholders, not just procurement and IT.

What in-house builds offer well

In-house AI builds can be valuable where the organisation needs deeper control, tighter integration, or unique differentiation. In-house builds can also provide better alignment with the organisation’s specific data and processes.

In-house builds often make sense for:

- Highly specific workflows where off-the-shelf tools do not fit well.

- Sensitive data contexts where control requirements are high.

- High-impact decision systems where transparency and monitoring are critical.

- Complex integration needs where AI must sit inside core operational systems.

- Competitive differentiation where AI is part of a unique product or service offering.

In-house builds can also support reuse across the organisation. A well-designed internal platform can provide shared components, monitoring patterns, and governance standards that reduce duplication.

The real burden of in-house builds

In-house builds create a responsibility that does not end at deployment. The organisation becomes responsible for model lifecycle management. That includes monitoring, drift management where relevant, change control, incident response, and ongoing improvement.

Common in-house build challenges include:

- Talent capacity to build and maintain systems reliably.

- Operational readiness to run models in production, including infrastructure and support.

- Governance maturity to document intended use, test properly, and monitor risk.

- Maintenance load as models and data sources evolve.

- Time to value which can be longer than expected, especially if data foundations are weak.

Many organisations underestimate this burden. They build something clever and then struggle to keep it reliable at scale. This is one reason hybrid models are increasingly common.

Hybrid delivery is often the practical default

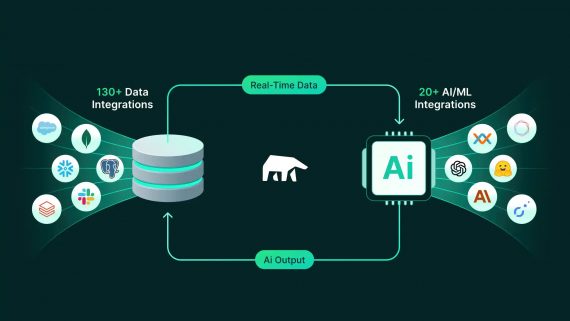

Hybrid delivery combines vendor tools and in-house capabilities. In many organisations, it is the most realistic approach because it allows the organisation to move quickly while still building long-term capability.

Hybrid models can take different forms:

- Using vendor AI for general productivity, while building bespoke AI for core workflows.

- Using vendor models through an internal platform layer that adds governance, logging, and monitoring.

- Using vendors for infrastructure and tooling, while owning models, prompts, and workflows internally.

- Building internal data and governance capabilities while relying on vendor AI for model performance and updates.

The advantage of hybrid delivery is flexibility. The organisation can select the right approach for each use case based on risk, value, and capability requirements. It also reduces lock-in because the organisation can shift components over time.

A practical decision framework

Choosing a delivery model becomes easier when organisations use a consistent set of criteria. Useful criteria include:

- Data sensitivity – how sensitive is the data involved and what controls are required?

- Decision impact – does this influence customers, regulated outcomes, or automated actions?

- Need for differentiation – is this a generic capability or a competitive advantage area?

- Integration complexity – does this need deep integration with core systems?

- Time to value – how quickly does the organisation need results?

- Internal capability – can the organisation build and run this sustainably?

- Change control needs – how important is stability and predictability of outputs?

For example, a low-risk internal drafting assistant might suit vendor AI, provided data controls are strong. A high-impact decision system might require more in-house control or a hybrid architecture with strong governance and monitoring.

Consider the governance implications upfront

Governance requirements should shape the delivery choice early. Some vendor tools may not support the logging, monitoring, or policy controls the organisation needs. Some in-house builds may lack the operational maturity to support auditability and incident response.

Governance implications to consider include:

- Ability to audit outputs and usage patterns.

- Ability to enforce access controls and data restrictions.

- Ability to manage and document changes over time.

- Ability to test and validate outputs in real workflows.

- Ability to respond quickly to incidents and harmful outputs.

If these implications are not considered early, projects often pause later, once scale triggers formal review. That is a predictable adoption slowdown pattern.

Beware of tool sprawl and inconsistent adoption routes

In large organisations, teams often adopt AI tools independently. Over time, this creates tool sprawl. Different tools with different risk profiles, different data handling rules, and different support models. Governance becomes harder, and duplication grows.

A hybrid approach can still be well governed, but it requires guardrails:

- A clear “front door” process for new AI tool requests.

- Approved tools for common use cases where appropriate.

- Vendor due diligence standards and contract requirements.

- A process for exceptions that is fast and predictable.

These guardrails reduce chaos without blocking innovation.

Think about long-term support and resilience

A practical question many organisations overlook is: who will support this in two years? AI systems require ongoing work. A vendor relationship requires renewal, governance updates, and change management when tools change. An in-house system requires maintenance, monitoring, and talent retention. A hybrid system requires integration management and clear ownership for each component.

When choosing a delivery model, leaders should ask:

- What happens when the model output quality changes?

- What happens when we need to change data sources?

- What happens if the vendor changes terms or capabilities?

- What happens if key internal staff leave?

Resilience is part of value. A solution that cannot be sustained becomes a future cost, not an asset.

A practical reference point for responsible scaling decisions

For organisations trying to align delivery choices with governance, capability, and adoption realities, it can help to work from a broad hub view of common programme considerations. This page provides approaches to scaling AI responsibly across themes that influence how AI is delivered and governed in enterprise settings.

The best delivery model is the one the organisation can sustain

Vendor AI can accelerate adoption, but it introduces dependencies and requires strong governance. In-house builds can offer control and differentiation, but they require sustained capability and operational maturity. Hybrid delivery often becomes the practical default because it combines speed with long-term capability building.

The right choice is not simply technical. It is an operating decision. It depends on the organisation’s risk posture, data realities, and capacity to run AI systems over time. When organisations choose deliberately, with governance and support in mind, they avoid the cycle of pilot sprawl and abandoned tools. Instead, they build a portfolio of AI capabilities that can be sustained, improved, and trusted as the organisation evolves.