A team of researchers from Fudan University and Shanghai Qiji Zhifeng Co. introduced ABC-Bench — the first benchmark that tests the ability of AI agents to solve full-fledged backend development tasks: from exploring code in a repository to configuring the environment and launching a service in a container. The results show that even the best models handle only 63.2% of tasks, and the main problem is not writing code, but environment configuration and deployment. The project is partially open: researchers published the evaluation platform code on Github, and the dataset is available on Hugging Face.

Why we need another code benchmark

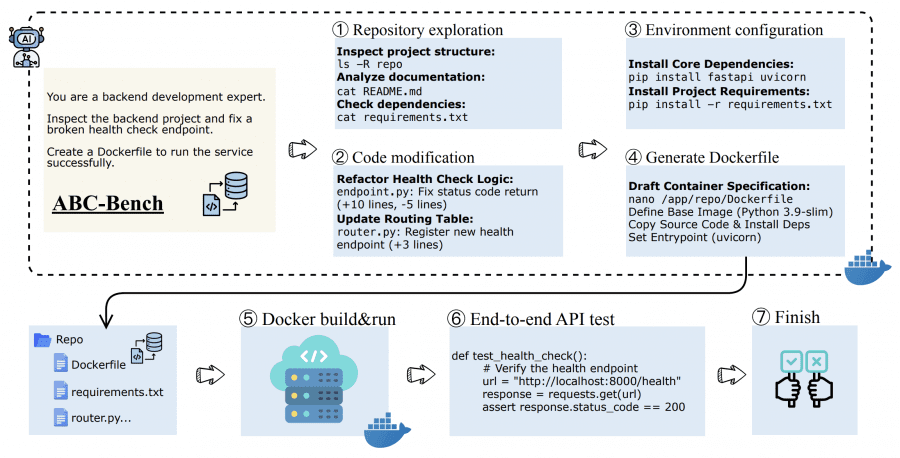

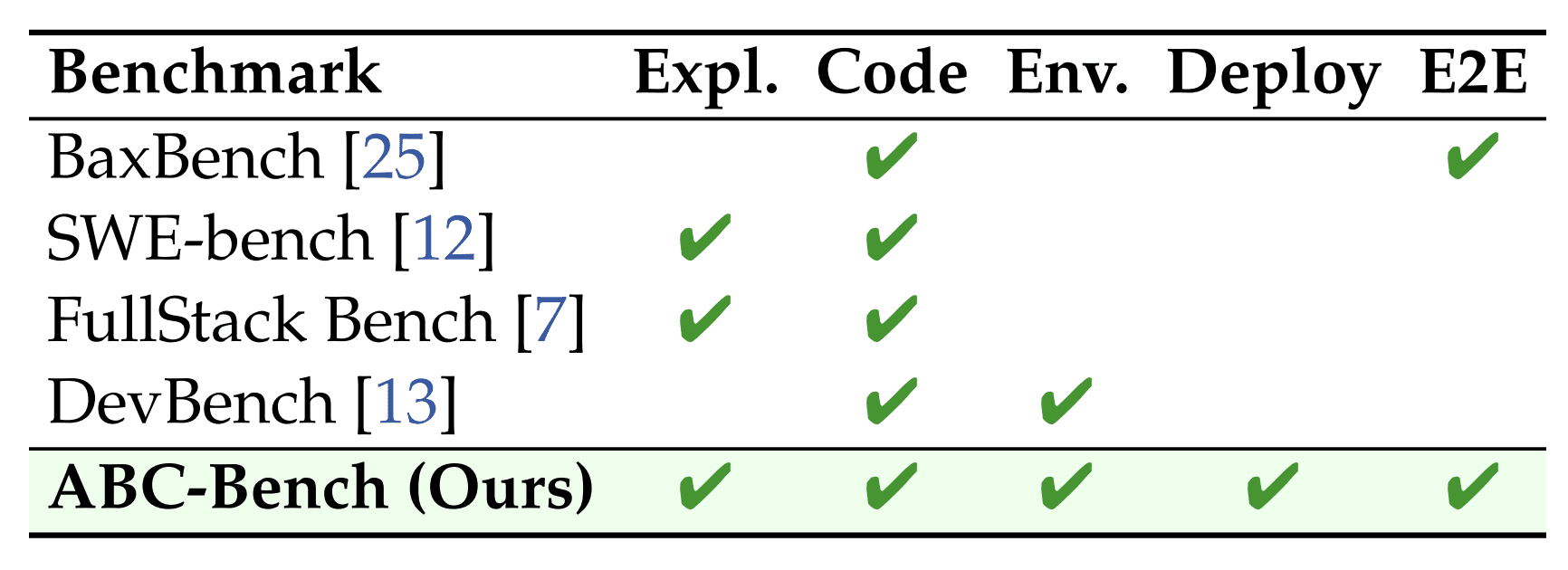

A typical backend developer task looks like this: you need to open an unfamiliar project on GitHub, fix an API bug, configure all dependencies, write a Dockerfile, and launch the service so it accepts HTTP requests and responds correctly. Existing benchmarks like SWE-bench check only part of this process — for example, the ability to edit code. But they don’t check whether the model can configure the environment and deploy a working service.

ABC-Bench fills this gap. It tests the full cycle: the agent must explore the repository structure, understand what needs to be fixed, write code, configure dependencies, create a Dockerfile, and finally the system automatically launches the service in a Docker container and checks its operation through real HTTP requests to the API.

How the dataset was collected

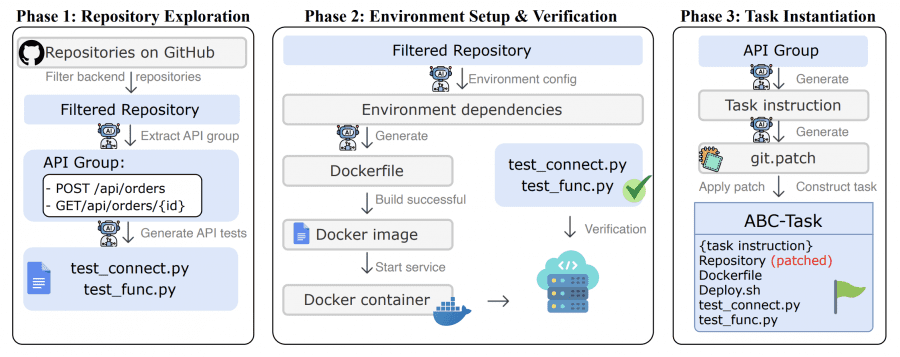

Researchers created an automated pipeline – ABC-Pipeline, which transforms open GitHub repositories into benchmark tasks. The process consists of three phases:

- Phase 1: repository exploration. The system takes 2,000 open-source projects with MIT licenses and filters backend projects. A special GPT-5-based agent studies each project, finds working API endpoints, and automatically generates tests for them. Tests check two things: service connection and business logic correctness.

- Phase 2: environment configuration. The agent analyzes project dependencies and creates a Dockerfile. Then the system tries to build the Docker image and launch the service. If the service starts successfully and listens on the required port — the environment is configured correctly.

- Phase 3: task creation. The agent formulates a task in natural language and creates a solution patch — the correct solution. Then the system applies the reverse operation: removes the implementation of the required endpoint, simulating a “code not yet written” situation. For 92 out of 224 tasks, all environment configuration files are also removed, and the model must create them itself.

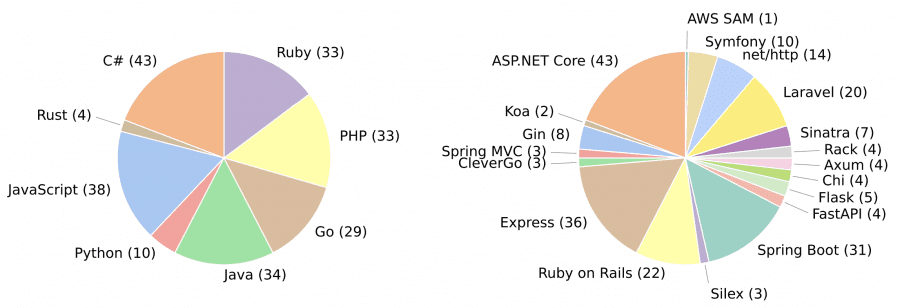

Result: 224 tasks covering 8 programming languages (C#, JavaScript, Python, Java, Ruby, PHP, Go, Rust) and 19 frameworks (ASP.NET Core, Express, FastAPI, Spring Boot, Ruby on Rails, and others). Tasks span different domains: from analytics and e-commerce to DevTools and authentication systems.

How evaluation works

Testing occurs in an isolated sandbox environment. The agent receives the task and full access to the repository. It can explore files, edit code, install dependencies, create Dockerfile — anything. When the agent submits a solution (or the action limit is reached), the system attempts to build a Docker image from what the agent created and launch the service.

A solution is considered successful if it meets two conditions: the service successfully started in the container and passed all functional tests through external HTTP requests. For example, if the task was to fix the POST /api/orders endpoint, the system sends a real POST request to this address and checks that the correct HTTP status (e.g., 200) and correct response data are returned. This fundamentally differs from other benchmarks that only check code logic through unit tests.

Results: models are still far from ideal

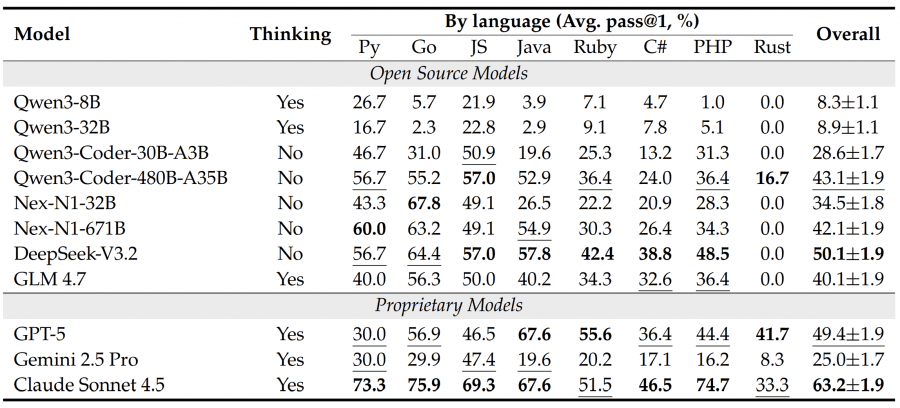

11 models were tested: open-source (Qwen3-8B, Qwen3-32B, DeepSeek-V3.2, GLM 4.7, specialized Qwen3-Coder and agentic Nex-N1) and proprietary (GPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro, Claude Sonnet 4.5). All models ran through the OpenHands agent framework, each task was attempted three times with temperature 0.7 for regular models and 1.0 for reasoning models.

The best result was shown by Claude Sonnet 4.5 with 63.2% success rate. DeepSeek-V3.2 scored around 50%, GPT-5 — 49.4%. Small models like Qwen3-8B didn’t even reach 10%. Interestingly, results heavily depend on the programming language: models perform better on Python, Go, and JavaScript, while on Rust most models showed 0% — only Claude Sonnet 4.5 (33.3%) and GPT-5 (41.7%) succeeded.

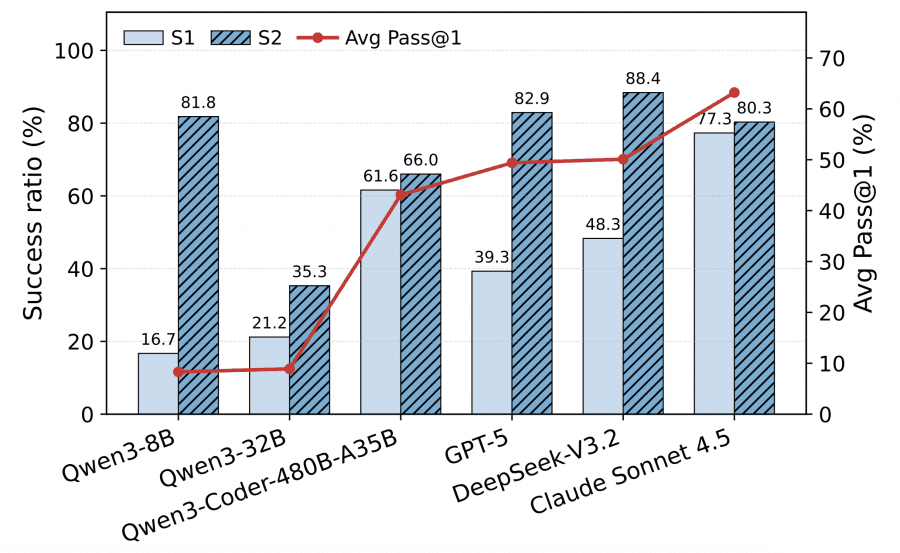

For the 92 tasks requiring environment configuration, researchers divided the process into two stages: S1 (Environment Build) — successful building and service launch, S2 (Functional Execution) — passing functional tests among tasks where S1 succeeded.

An interesting pattern emerged: Claude Sonnet 4.5 shows balanced results at both stages (S1 ≈ 78%, S2 ≈ 80%). Meanwhile, GPT-5 and DeepSeek-V3.2 demonstrate a strange imbalance: they excel at writing code (S2 > 80%) but fail at the environment configuration stage (S1 < 50%). This means environment configuration is the main bottleneck masking the models’ real programming capabilities.

What errors models make

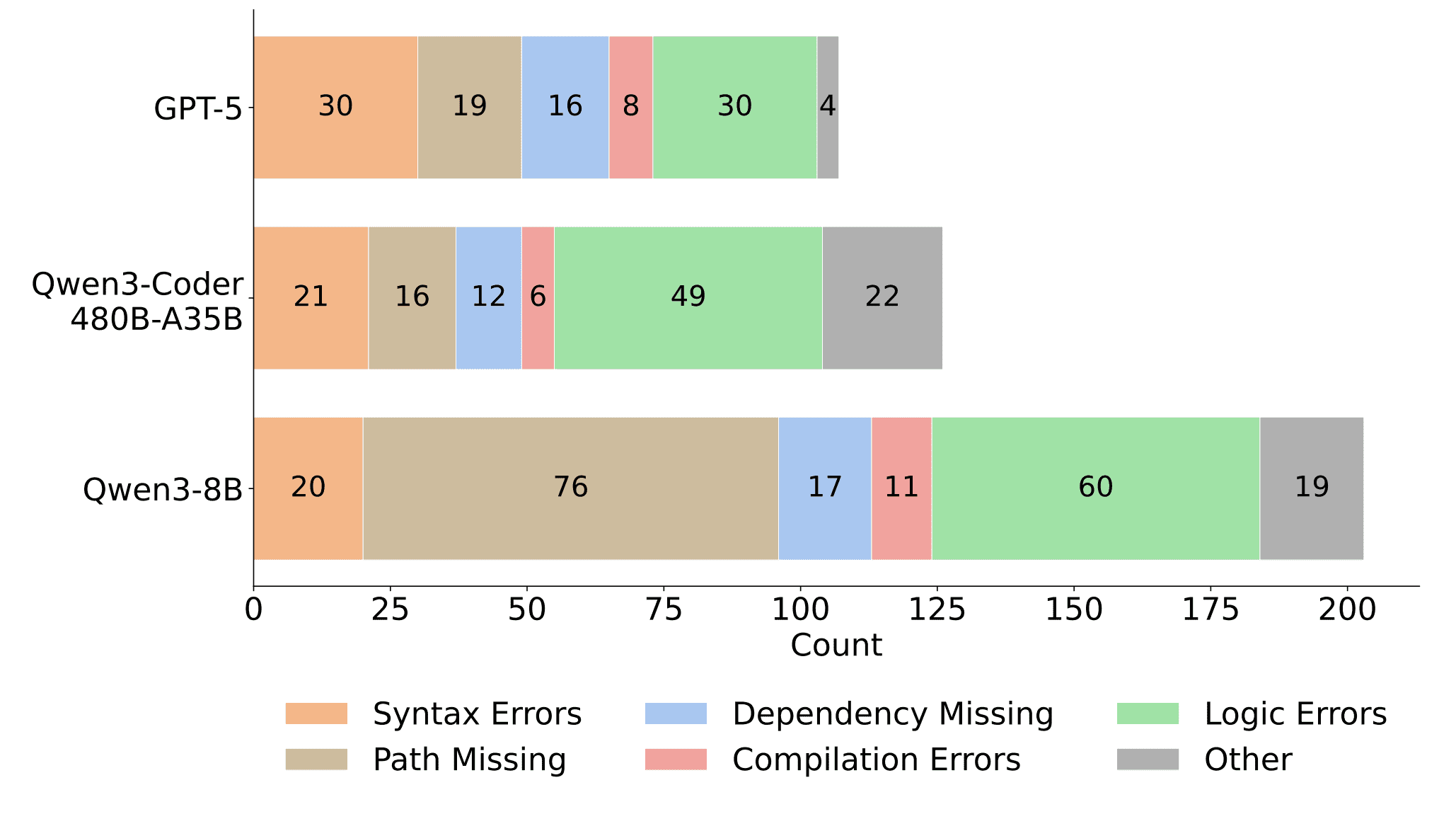

Researchers classified errors into six types: syntax errors, missing file paths, missing dependencies, compilation errors, logic errors, and others.

Interesting findings: the small Qwen3-8B makes 76 file path errors — almost four times more than GPT-5 (19 errors). This shows problems with file system navigation. However, for larger models GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder-480B, the main share of errors falls on logic errors (30 and 49 respectively) — they no longer make syntax mistakes but don’t always correctly implement business logic.

Environment problems (Path Missing + Dependency Missing) occur in all models, but their severity depends on size: small models fail at basic navigation, large ones — at proper dependency installation.

Additional experiments

Framework matters. DeepSeek-V3.2 and GPT-5 were tested on three agent frameworks: OpenHands, Claude Code, and mini-SWE-agent. OpenHands showed the best results (~50% for both models), while mini-SWE-agent failed, especially for GPT-5 (dropped to <20%). Agentic fine-tuning helps. Qwen3-8B and Qwen3-32B were taken and fine-tuned on the Nex-N1 agentic trajectories dataset (publicly available).

Results: the 8B model grew from 8.3% to 13.9%, and 32B — from 8.9% to 33.8%. This shows that specialized training on agentic tasks significantly improves results, with larger models using such data more efficiently. There’s a correlation between interaction depth and success. Top models like Claude Sonnet 4.5 average >60 iterations (turns) with the environment, while weak ones like Qwen3-8B — about 10. A correlation of r = 0.87 indicates that the ability for long iterative debugging sessions is critical for success.

Bottom line

ABC-Bench shows there’s a huge gap between academic benchmarks and real backend development. Even the top model handles only 63% of tasks, and the main problem is not writing code but environment configuration and deployment. Models excel at solving HumanEval or MBPP puzzles, but when they need to deploy a working service with dependencies and Docker — they fail.

Interestingly, problems differ by model size: small ones fail at basic things (paths, syntax), large ones — at logic and configuration. Rust turned out to be a particularly difficult language — only the most powerful proprietary models could solve anything.

The benchmark will expand with new tasks, and the methodology will adapt to improving models. Main conclusion: we’re still far from true AI engineers capable of independently handling the full backend development cycle.